Hudson Intelligence identifies and traces cryptocurrency holdings and digital assets to support dispute resolution and debt recovery.

We specialize in locating assets for civil and domestic lawsuits, judgment collection, corporate due diligence, bankruptcy proceedings, fraud restitution and law enforcement.

Our forensic investigators have joint expertise as Cryptocurrency Tracing Certified Examiners and Certified Fraud Examiners.

Locating Cryptocurrency for Creditors and Court Actions

Locating cryptocurrency and digital assets has become an important consideration for creditors and plaintiffs in court proceedings.

Cryptocurrency and digital tokens are owned by more than 20% of U.S. adults, including a disproportionate number of high-income earners, according to published studies. Investments surged in recent years as digital coins and tokens attained record-breaking prices and the total market size grew to more than a trillion dollars.

Hudson Intelligence assists clients by investigating, identifying and tracing digital assets. Our certified forensic investigators provide analysis on source, proof and disposition of funds.

In addition to our work for litigants and legal counsel, we have coordinated on criminal investigations and civil enforcement actions with the Federal Bureau of Investigation, U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, Commodity Futures Trading Commission, U.S. Attorney’s Office, U.S. Secret Service and state and foreign securities regulators.

Myth of the “Judgment Proof” Crypto Millionaire

Despite the relative popularity of virtual assets such as Bitcoin (BTC), Ether (ETH) and Tether (USDT), the market for cryptocurrencies and digital tokens remains hampered by myths and misperceptions. There is a false presumption that debtors who convert their fortunes to cryptocurrency have placed their personal assets beyond the reach of courts and creditors. Cryptocurrencies are not truly anonymous or untraceable; nor are these digital assets entirely secure from garnishment or seizure.

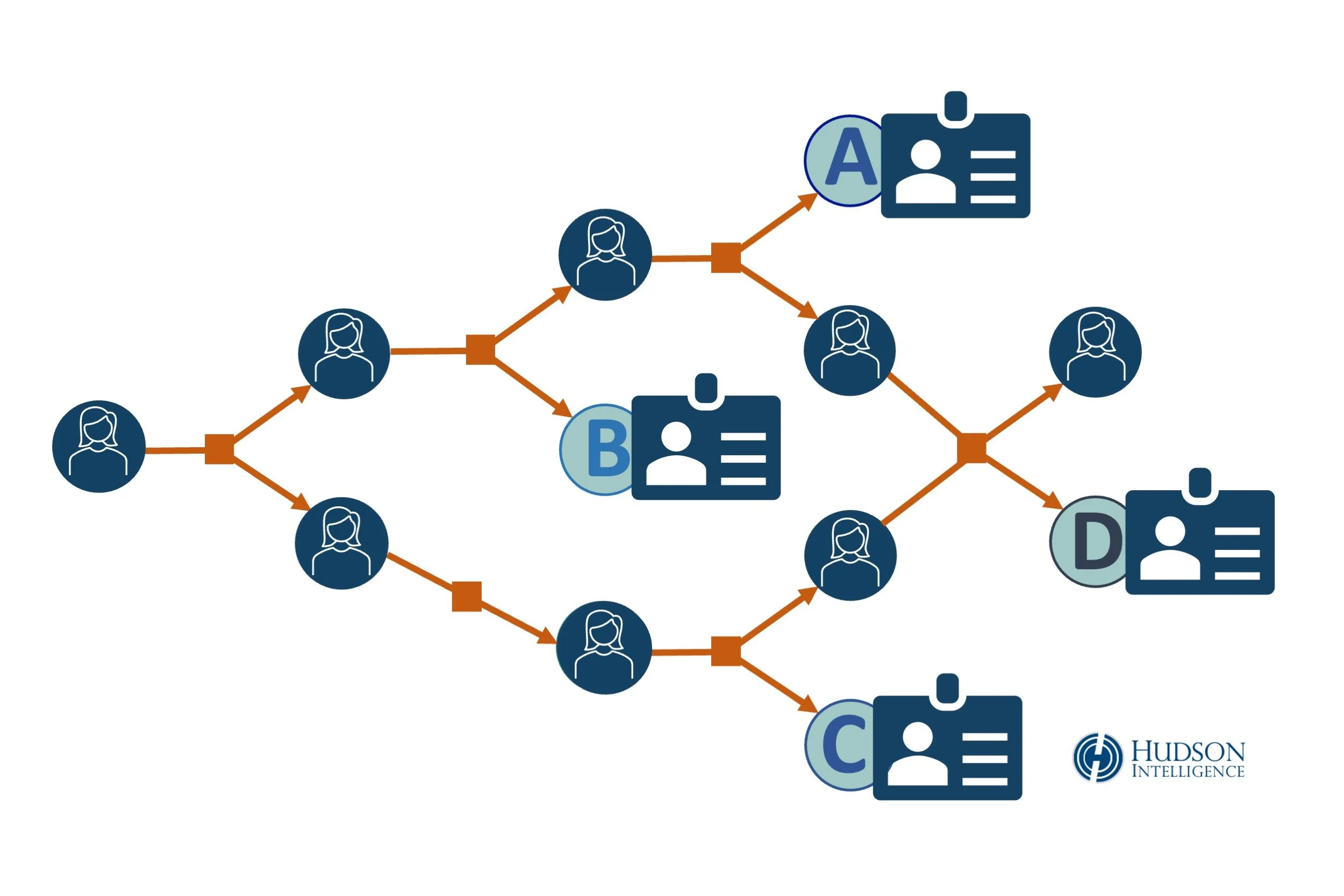

The conditions under which digital tokens can be successfully identified and traced are not well understood by many creditors and litigants. Cryptocurrency is pseudonymous: certain transactional details are publicly viewable on open-source blockchains, but the identity of the counterparties are expressed solely as long alphanumeric sequences known as ‘addresses.’ Deciphering coded entries on a blockchain – and turning them into actionable intelligence for a lawsuit or judgment – requires a well-credentialed investigator with specialized resources for cryptocurrency forensics. It also typically involves traditional tools of legal discovery such as subpoenas.

Investigation and Due Diligence of Digital Assets

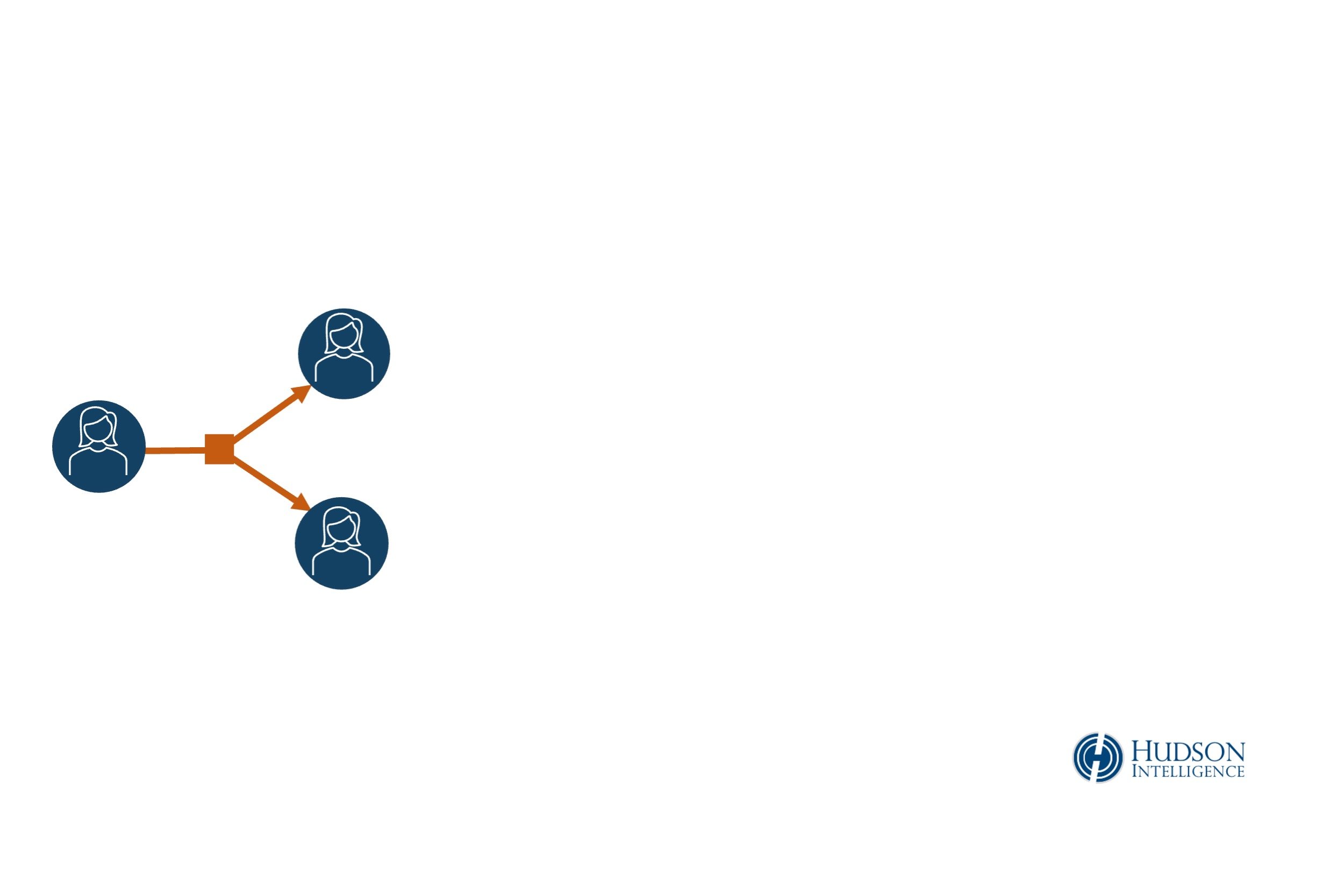

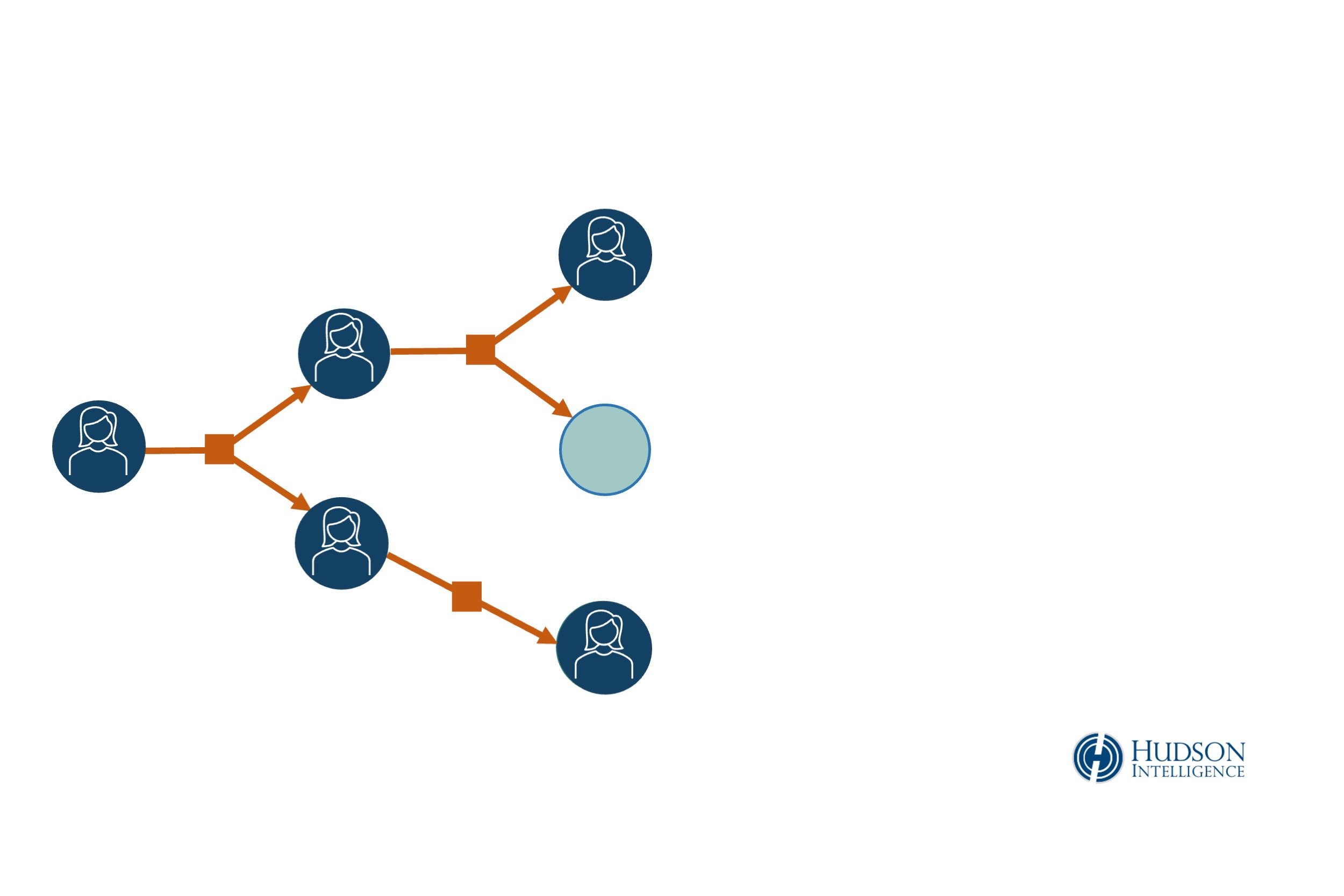

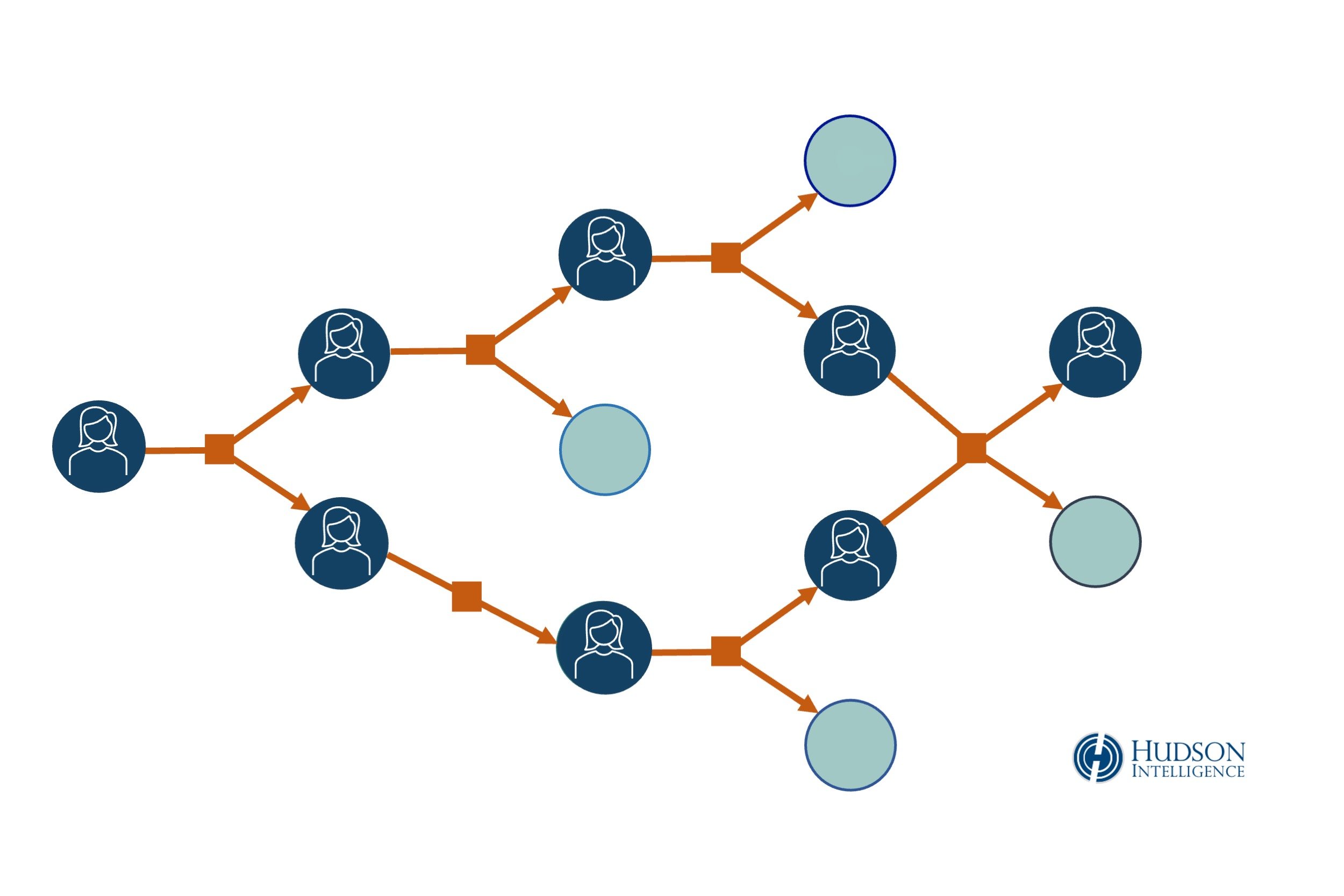

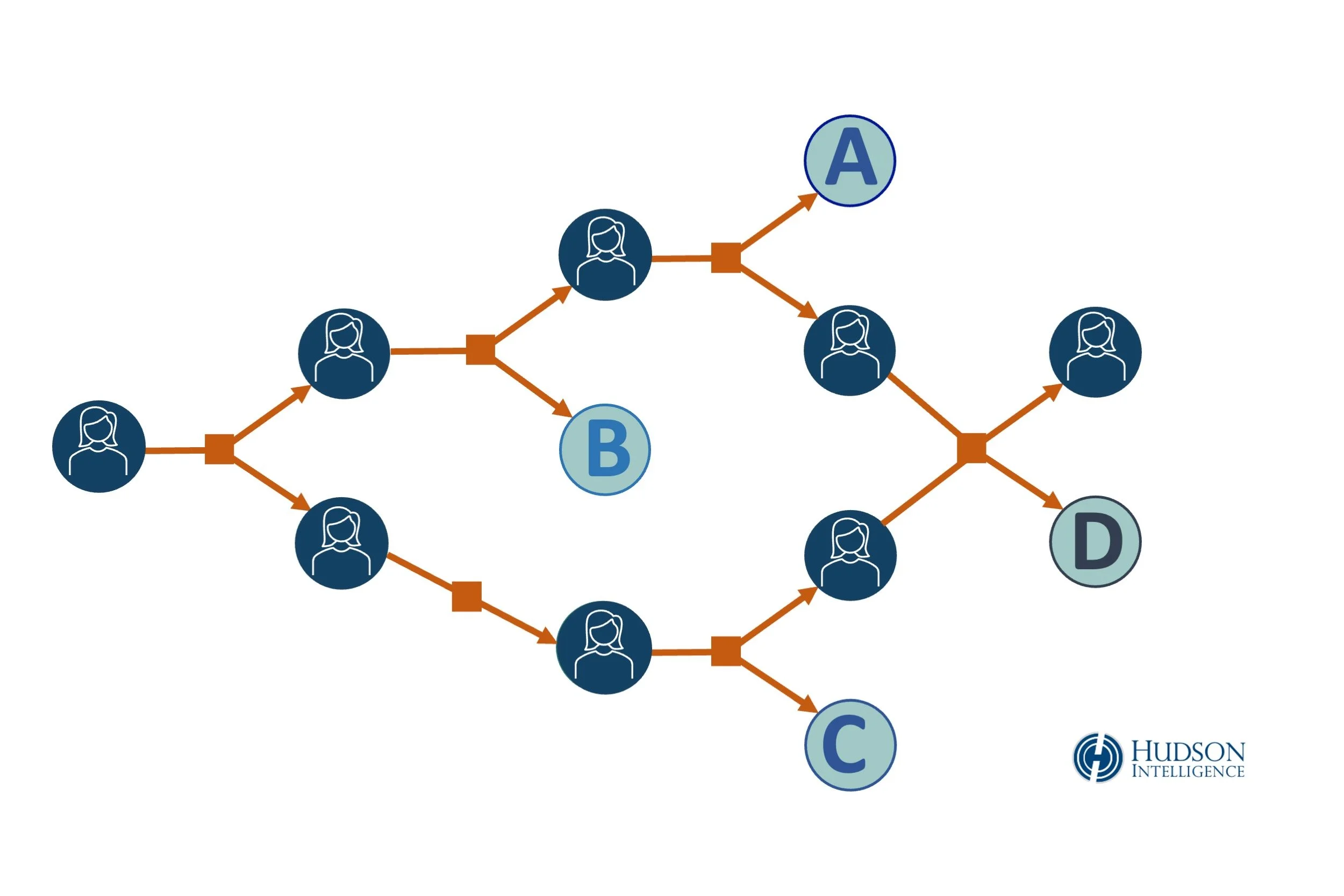

The investigative process for locating cryptocurrency and digital assets depends, in part, on the nature of information available at the outset. If a creditor is aware of specific wallet address(es) used by the subject, forensic investigation can proceed directly with efforts to trace relevant transactional history. The objective will be to determine current location and value of active holdings. Investigators will also seek to identify clusters of other wallet addresses under common control, as well as any recent transactions or account activity with commercial exchanges and virtual asset service providers (VASPs).

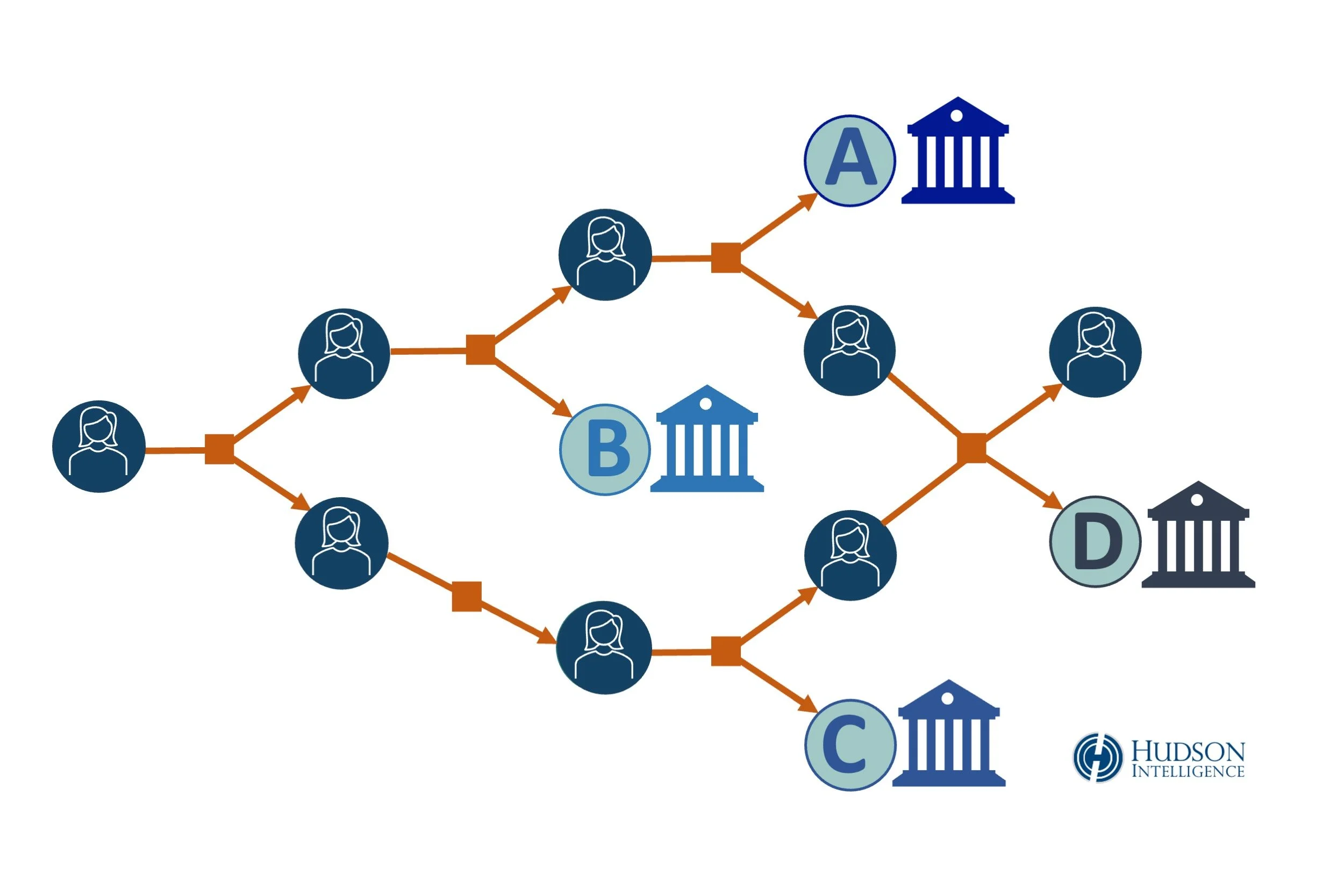

Commercial exchanges like Binance and Coinbase store extensive records of on-chain transactional history for accountholders, including buy, sell, trade and transfer activity. They are often linked to the owner’s bank accounts at other financial institutions. Successful garnishment and subpoena of a well-funded, highly active exchange account can yield a wealth of information for judgment enforcement.

In certain cases, it can be possible to determine the existence of debtors’ trading accounts with major exchanges – or identify their wallet addresses for a forensic trace of digital assets – even if the client does not possess any crypto-specific knowledge of the subject at the outset of an investigation. Such inquiries rely on a mix of proprietary methods, blockchain intelligence and investigative resources, including open and non-public sources.

Supplementing a Forensic Investigation with Subpoenas

Depending on the extent and complexity of debtors’ cryptocurrency holdings, investigation of their undisclosed digital assets may require multiple stages of investigation and legal discovery. For example, initial investigation might identify account activity at a major exchange in the U.S., and subsequent analysis of account records and transactional history from that exchange – once obtained under subpoena – could produce leads to assets transferred to the custody of other exchanges. Cryptocurrency and digital tokens may also be invested through decentralized finance (DeFi) firms and other third-party services, which may also be appropriate targets for collection efforts.

Property, Securities, Commodities or Currency?

Virtual currencies are considered to be "property" by the Internal Revenue Service for federal tax purposes. Similar to other forms of property, cryptocurrency and tokens can be seized by a creditor to satisfy a judgment.

In different contexts, the precise legal nature of cryptocurrency varies depending on the perspective of the examiner. For example, the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) and federal courts have found that virtual currencies are commodities under the Commodities Exchange Act (CEA), while enforcement actions by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) have characterized a number of digital coins and tokens as securities. Securities and commodities are types of financial instruments that can be seized for judgment enforcement.

Cryptocurrencies are also, quite simply, a digital form of currency. Accordingly, many states regulate cryptocurrency exchanges and virtual asset services under existing statutes for money transmitters. Money transmitters are also generally required to register as “Money Service Businesses” (MSB) with the U.S. Department of Treasury by filing through the BSA e-Filing System. Public registries of state and federal regulatory agencies can provide useful information for determining where to serve subpoenas and writs on exchanges.

Garnishment of Cryptocurrency: Logistical and Legal Challenges

Creditors and attorneys who are accustomed to serving garnishments on major banks and financial institutions may discover new challenges when pursuing cryptocurrency assets. Below are several circumstances in which the treatment of digital assets deviates from traditional practices to collect debts in dollars and cents:

Self-Custody Wallets: Privacy concerns prompt many crypto enthusiasts to take extra precautions to safeguard their anonymity and assets. Such concerns run high among debtors seeking to avoid collections, as well as criminals seeking to evade prosecution.

Rather than holding digital assets in a wallet hosted by a commercial exchange such as Coinbase or Kraken – which are more vulnerable to garnishment – more privacy-conscious parties utilize off-exchange (or offline) alternatives, such as hardware wallets, software wallets, mobile wallets and paper wallets. These self-custodial wallets hold private keys that control cryptocurrency transactions, thereby limiting authority over those assets exclusively to the person who possesses the wallet. This greatly reduces – or eliminates – the risk that those assets will be surrendered through garnishment or seizure order on third-party service providers.

However, even the most stringent privacy precautions might not make crypto assets impervious to collection. A post-judgment debtor examination could include questions pertaining to private keys and passwords (as well as any seed phrases for password recovery) used by the debtor in their self-custodial wallets. Relinquishing the private keys effectively yields control over the corresponding assets, which could then be transferred per court order to the creditor’s wallet.

Federal law enforcement agencies have also utilized other methods – which do not involve direct examination of the defendant – to seize billions of dollars of Bitcoin and other digital assets. Their methods and tradecraft have not been publicly disclosed, but potentially involve recovery of private keys through subpoena of web servers and telecom carriers, exploiting sloppy password management and other technical mistakes made by cybercriminals.

Quasi-Compliant Exchanges. There is a distressingly wide range of compliance standards among exchanges and virtual asset service providers. Commercial exchanges generally employ some degree of compliance practices familiar to banks and other financial institutions. These practices include Know Your Customer (KYC), Anti-Money-Laundering (AML) and Anti-Terrorist-Financing (ATF) guidelines, as well as routine filing of Suspicious Activity Reports (SAR) and Suspicious Transaction Reports (STR) with financial regulators. Legitimate exchanges with previously strong internal compliance standards have reduced their staffing levels during market downturns, which can adversely affect whether – and when – they respond to formal requests for information. It is not uncommon for attorneys to wait 12 months for a formal response in some circumstances. Law enforcement inquiries may receive quicker responses than civil subpoenas; and multi-million-dollar claims may be prioritized over information subpoenas or small-value garnishments.

High-Risk Exchanges. Other exchanges may be characterized as “high risk” due to absence of legal, financial and regulatory compliance. These exchanges generally fail to verify customer identities or prevent the creation of fraudulent accounts. They do not engage in illicit transactional monitoring or prohibit participation by sanctioned parties. High risk exchanges frequently fail – or outright refuse – to respond to subpoenas or warrants.

Decentralized Exchanges (DEX): In contrast to major commercial exchanges with large staffs and centralized controls, decentralized exchanges (DEXs) operate in an automated fashion to ensure mutual anonymity between both sides of cryptocurrency trades and swap transactions. Many of these peer-to-peer exchanges are fully automated through smart contracts, which are computer scripts that run on the blockchain. They tend to operate without KYC controls, and without taking custody of counterparty assets, potentially rendering them useless for information subpoenas and collection efforts.

Offshore Jurisdictions. A number of exchanges are domiciled offshore in countries such as Seychelles, and certain compliance departments are known to refuse to disclose records or freeze accounts without an order from a local court in the same jurisdiction.

Co-Mingling in Corporate Accounts. Although the IRS considers cryptocurrency to be property for taxation purposes, digital coins and tokens are not stored like bricks of gold bullion in vaults at the major exchanges. These are virtual assets, digital representations of value without physical form. Customers’ coins and tokens are not FDIC-insured and are often co-mingled within an exchange’s internal accounts. Bankruptcy proceedings of exchanges Celsius and Voyager Digital have shown that the pool of funds from customer accounts might be treated as corporate, rather than custodial, assets.

Non-Surviving Exchanges. A few major exchanges such as FTX have imploded into insolvency amid allegations of fraud or market downturns, making their customer assets and related transactional records extremely difficult, if not impossible, to recover by a creditor or debt collector.

Money Laundering. There are a multitude of tools and techniques for obfuscating the auditable trail of digital assets, including layering, mixers, tumblers, peel chains and more. Whether used for financial privacy protection by law-abiding libertarians – or money laundering of tainted crypto by international crime syndicates – these methods are intended to make it more difficult and time-consuming for blockchain investigators to trace the flow of funds. They can also frustrate collection efforts. More information on the technical side of cryptocurrency forensics is provided on our website on financial fraud investigation.

Successful investigation of cryptocurrency and digital assets often requires awareness and analysis of money laundering activities. Layering, for example, is a method in which funds are moved, mixed and co-mingled across a constellation of intermediary wallet addresses under common control. Although more frequent in criminal cases, similar efforts to conceal assets may also be seen in civil and domestic actions.

Consult an Investigator

If you would like to discuss a cryptocurrency investigation for asset discovery, judgment enforcement or related matters, please complete the form below.